Exploring Mexican Identity Through Art At The National Museum of Mexican Art

One of Chicago's "hidden gem" museums which houses especially prescient work given the influx of migrants throughout 2024

ARTSVISUAL ARTEXHIBITONS

5/28/20246 min read

Mexico, as a nation and culture, has a unique aura, that takes the form of an almost magical emanation from both the land and the people. Within spaces like Chichén Itzá, Jalisco’s Bosque La Primavera or Los Guachimontones of the Teuchitlán Culture site, there is a resonance that carries the tone of thousands of years of collective history. The warm Mexican breeze whistles with the whispers of Olmec, Aztec and Mayan empires, The Grito de Dolores spoken by Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, and the neighs of the Zapatistas’ horses.

Despite the United States’ reputation as the world’s melting pot, its segregation generally dissuaded the intermixing of people from different cultures. This resulted something more akin to a stew: multiple distinct ingredients that don’t necessarily emulsify but do come together to create a coherent dish. Mexico, on the other hand, could be considered the true melting pot of the Americas – where indigenous Mexicans mixed with European, African, Chinese, Lebanese, and Jewish people as distinct groups migrated to the country at different times throughout the last four centuries. Despite the diversity of the incoming groups, Mexico was successful in integrating these immigrants into their country and culture, whereas the United States generally sectioned newcomers off into pockets of distinct ethnic neighborhoods.

The history of Mexico within the current era is one of revolution and reform, defined by populace movements against powerful systems of oppression both at home and from abroad. As control of the land continuously changed hands throughout history, bloodlines intermixed, traditions were adopted and adapted, and arts & culture faced a near constant redefinition. With each conflict came both the deconstruction and restoration of values and norms, where long periods of intense tumult were followed by periods of extreme optimism and both structural and spiritual reconstructions. The National Museum of Mexican Art, located in (and due to their partner Yollocalli’s mural program, throughout) Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood, uniquely captures this atmosphere in both its works and its unique context that relates art with evolution of Mexican identity throughout the last five centuries.

Currently, the museum is divided among 4 temporary exhibitions spaces (currently showing Ancient Huasteca Women, Arte Diseno Xicao II, Mariachi Potosino, and Yollocalli Class of 2023) as well as a perpetual set of galleries called “Nuestras Historias: Stories of Mexican Identity from the Permanent Collection”. While all of the exhibitions are supremely important, the cognizant and intentional curation of the perennial collection was the most striking and prescient aspect of the museum.

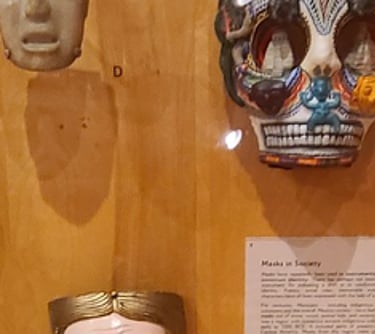

The permanent collection contains an amazing mixture of visual art created throughout the last 500 years while providing a historical narrative and journey through different periods in Mexico’s history. The collection begins with recent depictions of ancient indigenous mythology, paintings documenting archeological discoveries at Chichén Itzá, an assortment of antediluvian and reproduced masks, and folk art carvings and candelabras that were crafted in a style that is still popular to this day. Further into the exhibition, the influence of Spanish colonialism is highlighted through the adoption of Catholic imagery and subjects in works collected from the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. The sequence of artwork continues chronologically through the social reformations following both the Mexican War of Independence and the later Mexican Revolution, showing a reclamation of the national identity that incorporated popular culture as well as romanticized the indigenous themes of embracing natural landscapes, respecting native fauna, and affinity towards mystical surrealism.

Jesús Helguera (1910-1971), La leyenda de los volcanes (The Legend of the Volcanoes)

As technology evolved and fostered a rapid transnational exchange of information, Mexican art began to employ both the socially progressive themes and abstract imagery that defines the second half of the 20th century, while maintaining a distinctive cultural identity unique to the Mexican ethos. This is highlighted in the back half of the museum, with works featuring a variety of notable Mexican artists over the last 70 or so years – including more recent sculptural and glassworks that incorporate some tongue in cheek humor like Rubén Ortiz Torre's customized and kitted out “dancing” lawnmower piece entitled “The Garden of Earthly Delights”. The final room of the exhibition is a showcase of art’s role in supporting social justice movements, highlighting prints, murals, and posters that were used to illuminate movements across workers’ rights, political activism, and the rejection of Eurocentric influence.

Some imagery persisted throughout the arch of time highlighted throughout the permanent collection including animals native to the land, skeletons (both la Catrina and simple skulls and bones), and vibrant color schemes that seem to dance from the canvas. These symbols persisted through eons - from the Huasteca carvings to paintings released in the last decade - indicating a deep connection to the ethos and an eternal part of the Mexican identity. The museum excels in exploring the evolution of Mexican art throughout the history of the country, building a timeline from the pre-colonial to the modern era while detailing the cultural forces driving the creative output of the various periods.

Beyond just imagery, certain subtle cultural themes are evident across the epochs of Mexico’s history. An appreciation and reverence for the land was palpable, even true during the emergence of Catholicism where the majority of art both commissioned and preserved had to adhere to strict religious dogma – in Mexican art, saints and other religious figures were often portrayed in outdoor settings and with animals. The communal aspect of the culture was also on display, with pieces often focused on groups instead of individuals while immortalizing moments that shaped the history of the nation, from supernatural episodes passed down through indigenous mythology to later social justice movements in the late 20th century. Spirituality and mysticism is featured across eras, religious philosophies, and artistic mediums - reinforcing the idea that there definitively is magic in terra of this cradle of civilization.

The Ancient Huasteca Women and Yollocalli Class of 2023 exhibitions were conceptually welcome compliments to the permanent collection as it highlighted both some of the earliest examples of art in Mesoamerica as well as modern pieces created by Chicago youth. The search for personal and collective identity was evident even in 1500BCE through the preserved jewelry on display and the body modification documented in the subjects of the sculptural work. This contrasted well with the work of the young people who were part of Yollocalli’s exhibition. Though the works were conceptually varied and covered disparate themes, the energy of teenage years, where personality is becomes calcified, was palpable throughout the works.

As the name implies, Nuestras Historias is an enlightening journey throughout the history, artistry, and psychology that continues to shape the fluid cultural identity of Mexicans both within the country and abroad. The exhibition does a wonderful job highlighting the threads of tradition that come together to form the tapestry that is Mexican identity among indigenous tradition, multiple reformations following periods of social upheaval, the communal ethos so ingrained in the culture, and the alternating adoption and rejection of Eurocentric influences throughout the second half of the millennium. Overall, the Museum is somewhat of a hidden gem - in Chicago’s revered Pilsen neighborhood which highlights Hispanic contributions to both the city and the world at large – and especially prescient reminder given the continued influx of migrants during the ongoing crisis. The National Museum of Mexican Art is always free to the public and is well worth a stop when visiting Chicago's Pilsen neighborhood or if looking to understand Mexico's contribution to global arts and culture.

Left (or top on mobile): Alfonso Castillo Orta "Mask with pre Cuahtemoc figures" Right (bottom): Display of masks dating back to the 200 C.E through the early 1990s

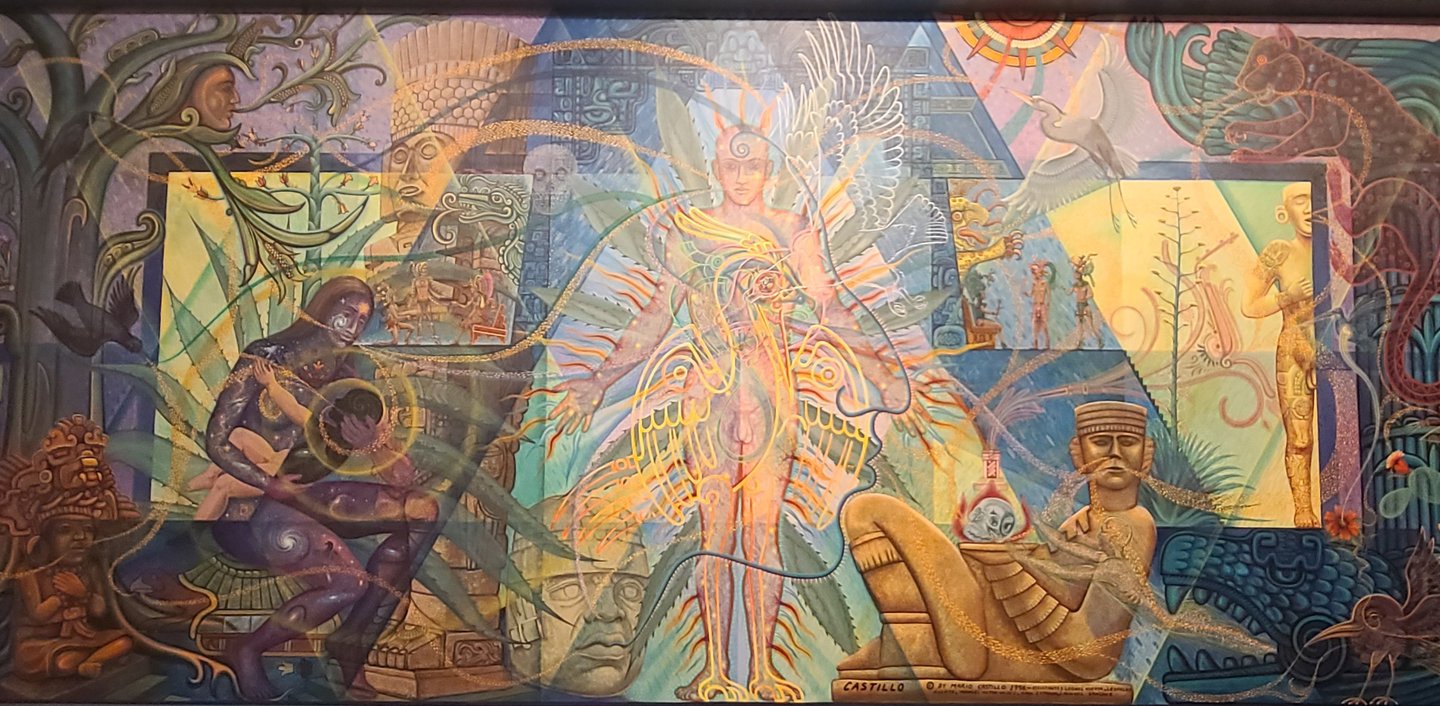

Mario E. Castillo, "Las memorias antiguas de la raza del maguey aun respiran"

Display of miniture sculptures depicting Huasteca Women

Mural outside of NMMA as part of Yollocalli mural project